Cutting edge child development theorists are calling for the tearing down of the traditional adult-child relationship. Come here to learn what the research shows, and how you can use these summer camp ideas to make your camp the most fun, safest, and nurturing place on Earth.

“I’m a dude,” he said. Lessons from a Transgender Summer Camper.

What I learned about kids, camp, and myself from a camper who “came out” as transgender. All names changed to ensure privacy. This summer we had the pleasure of working with a young man who has spent his whole life being called a girl. You can’t blame people, I suppose. After all, he was born with female anatomy. But that inner voice inside his head? It had been telling him something else. His birth certificate says, “Christine,” but he prefers Chris. He preferred Chris last summer, too, but never told us why. You see, until this summer, only a few people knew that Chris identifies as a male. When he came to camp this summer, he told his counselor on the first day that he was a male, but asked that counselor not to share. On the second day of camp, the counselors in Chris’ lodge had all the campers seated, and were asking the campers if there was anything they thought the group should know about them to help everyone have the best time possible. You know – pet peeves, stuff that grosses them out, or to warn other people that they snore. That’s when Chris piped up. “I’m a dude,” he began, “And I don’t care if everyone here knows it.” The other girls in the lodge simply nodded. Everyone moved on. A little while later, two other campers revealed that they, too, identified as something other than one of the binary genders. They called themselves “gender neutral,” and asked that we used gender neutral pronouns. Even at a place where acceptance is the norm, and not the rule, I was a little nervous. I felt so protective of these young people, and so grateful that they felt comfortable enough to share these huge parts of themselves here at camp. But when that first joke was let slip, what would I do? It never came. I learned that kids are a lot less old timey and out of touch than I am – that this news was hardly news at all. Chris and his friends were just people. Cool, interesting people. Normal campers. Chris’ week at camp looked pretty much exactly like his weeks from previous summers. Hanging out with friends, drawing, talking about TV shows, and telling inside jokes. Life was great. Week 2, and a whole new experiment Then, Saturday came. Most of the kids at camp were leaving, and some were staying for another week. One of those was Chris. I talked with one of the counselors who had connected with Chris the most. We blessedly found out that this counselor identified as gender-queer very early in the summer (hooray for diversity!), and so these two had a very special bond. “How was Chris’ week? Did everything seem like it went well?” I asked. “Yeah, for sure. Chris seems to be doing great. He’s really looking forward to next week,” the counselor responded. “Awesome, I will be finishing up housing shortly and I’ll let you know where he is staying.” HE is staying. I had already assigned Chris to a girl’s lodge. “Say, do you think Chris would prefer to be in a boy’s lodge, or a girl’s lodge?” I asked. The counselor paused for a second. “I’m not sure. He’s pretty new to...

read moreHelping Kids Realize They’re Good

The 5 Silver Bullets to Ending Bullying Part 3: Growth Mindset Acknowledgement When we talk about bullying, we so frequently get bogged down in dealing with it once it’s already happened. And even a lot of the preventative measures that are suggested seem to be “band-aid” measures. Let me explain what I mean. I recently spoke with Dr. Randall Grayson (the director of the magical Camp Augusta) regarding different counseling techniques, and he emailed me the following: “There is nothing wrong with one’s self-expression of beliefs, as long as it is not offered OR heard with the idea that following such a belief is to be done BECAUSE of who I am, or someone else is, or some power structure. A change in behavior due to respect and rapport is quite different than one due to desiring/contingent relationship or favor, or blind obedience.” In other words: We don’t want kids to behave because they’re worried about what we think of them. A powerful statement, and contrary to a lot of what I’ve read (and taught!). But as I worked the idea over in my mind, I realized it was very much in line with a lot of what I already believed. A person’s behaviors are only modified in the long term if they feel motivated to modify it. Forcing people to go to drug rehab, for instance, is notoriously unsuccessful. Felons are incarcerated after being released from prison at a startling rate. So how do we help children become motivated to “do good?” Enter step 3 in our silver bullets to curb bullying – Growth Mindset Acknowledgement. Why did Jason hate Ga Ga? To start, we’ll consider the story of a child we’ll call “Jason.” Jason came to Vanderkamp very excited to play one of our most popular games: Ga Ga. After the first game, I was puzzled as to why he looked forward to it so much. Jason was never more upset than when he played Ga Ga. Perhaps 75% of the time that something bad would happen to him in the game, he would sit down in a heap, sobbing into his hands. When asked what was wrong, he would scream accusations at other players and curse his misfortune. Even “winning” the game provided him no great relief, as a win was seen as something that should happen, not as a special occurrence. It was easily the most glaring example of bad sportsmanship I have ever seen. What was going on? Enter the psychologist Carol Dweck, a psychology professor at Stanford University, made an incredibly important contribution to child development theory that helped us unravel things. In her 2006 book, Mindset, she suggests that many people in the world suffer from the idea that there are “fixed” qualities about them that are unchangeable. People with a fixed mindset believe that there are many innate qualities about them, that when taken as a whole, sum up their total worth. Many people have a tendency to think they have a certain amount of academic ability, or creativity, or kindness, or patience – when in fact we have plenty of evidence that suggests all of these traits can be actively cultivated. So why do people hold on to the illusion that these things are fixed? Dweck suggests that we are...

read moreHow do summer camps avoid becoming stagnant?

The real keys to a dynamic summer camp culture If you’ve been a part of any camp for long enough, you’ve inevitably seen someone bristle at the idea of changing something about that camp. Sometimes it’s a big thing (should we do small group camping, or large group camping?). Sometimes, it’s a smaller thing (should we hold swim checks on Sunday, or Monday?). Either way, change at camp is hard. We love our camps, and we don’t want to lose who we are, and what has made our camp something special. But how do we keep being “us” while not growing stagnant? The answer may just be found in developmental psychology. Changing our mindsets In 2006, Carol Dweck wrote a book called Mindset, which has fueled no shortage of discussions at camps and other institutions across the country. If you haven’t read the book, a great summary can be found here. Essentially, she puts forth that there are two ways of conceiving of ourselves – via the lens of having a “fixed mindset” or a “growth mindset.” Fixed mindset folks tend to view human beings as static. In other words, they believe that people are born with a certain amount of intelligence, or creativity, or work ethic, and that our lives are basically determined by what we are born with. Growth mindset people tend to view human beings as dynamic. They believe that while we are all born with certain qualities about ourselves, we actually have the ability to change and adapt based on the circumstances we are presented with. There are a number of extremely valuable applications to these ideas, both as we think of ourselves, and as we think of others, but the primarily application for institutions that work with young people seems to be this: Telling kids they are valuable based on aspects of themselves they can’t control (i.e., if they are smart or not, or fast or not, or good looking or not), can make them feel helpless. Therefore, communicating with children about things they CAN control can make them feel empowered (i.e. – how hard working, or kind, or generous they are). For the most part, both scientific and anecdotal evidence finds tremendous benefit in treating others (and ourselves) this way. But when I first started working at summer camp, I found that while I had internalized these ideas as they pertained to human beings, I hadn’t internalized them as they applied to my own worldview. I’ll explain. ”I’ve become a teacher.” When I was getting certified to be a high school English teacher, I had this idea that earning my degree would mean that I had “arrived.” At that point, I’d go out to high schools, and teach a bunch of students things that I knew and they did not. Knowledge was this thing I could go find, and once I had it, I was all set. In my (very brief) teaching career, I didn’t see a lot of opposition to this idea. I was the teacher, they were the students. I had the knowledge, they needed the knowledge. Back to camp. Like a lot of you, I went to a camp that I thought was incredible. It had changed my life, after all, and there were all these other people who shared...

read moreFive Silver Bullets to Stopping Bullying: Step 2 – Allow for Mixed-Age Interactions

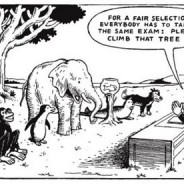

A lesson learned from our ancestors on the benefits of mixing ages at summer camp If you missed Step 1 – Transcending Supervision, Check it. The segregation of children into age-specific groups has become so ubiquitous in our society that we hardly even notice it anymore. From the time children are born, they are placed into care with other children of a similar age. Whether it happens in school, or sports, or camp – the message that association with others of the same age is normal is reinforced again and again. Thus, when I first encountered an article about mixed-age play, I was dubious. Why, if there were so many benefits to mixing kids of different ages, was society so rigidly structured for age segregation? I had the usual list of objections, as well. Wouldn’t the older kids be bad influences on the younger kids? Mightn’t they bully them? Would it even be fun for anyone involved to have all those young or old kids around, at completely different developmental stages? Well, I was pretty set in my ways until I encountered this now famous video by Ken Robinson and the folks behind RSA animate. It shined a light on how crude it was to force children to move along together just based on the year they were born. I did a little more digging, and when I did, my opinion on mixing ages was changed forever. I’d love to share what I’ve come across, and how it’s helped us curb bullying at summer camp. Prehistoric Man, teaching us yet again The first article I encountered sold me on the idea of mixing age groups immediately – a brief article by Peter Gray in Psychology Today. He cited a combination of anthropological research and modern day research that I found absolutely fascinating. The first won’t surprise you – our prehistoric ancestors had little use for age segregation, and there is no evidence that any society before the creation of the modern schools in the late 1800s that strict age segregation took place at all. The human race organized itself in mixed aged groups essentially forever, and then some well-meaning educational theorists in the 1800s decided to try something new. And we’ve done the same thing ever since, essentially without questioning it. The next piece surprised me, though. Peter Gray went to the original Sudbury Valley School in Framingham, Massachusetts. Sudbury Schools are more widespread now (and we actually invited a Sudbury School up to our camp for a few days each of the last few years – they make ideal midweek retreat groups since they don’t have classes!), but the original concept was truly groundbreaking at the time. Sudbury Schools basically do what we do at camp – except they do it all year long. Now, I could (and probably will) write a whole 5,000 word post on the idea of just allowing kids to do summer camp all year long, but this post is specifically about something else, so I’ll at least make a token effort at staying on topic 🙂 When Peter Gray went to the Sudbury School to research, he found what I believe to be a very important and surprising social structure. He writes: We found that more than half of the social interactions among...

read moreFive Silver Bullets for Dealing with Bullying – Step 1: Transcending “Supervision”

Zero tolerance for Zero Tolerance, a few ounces of prevention, and a pound of cure. Hi. This is a 5 part series on effectively preventing the formation of a culture of bullying at your camp. I’ll share this intro in all 4 steps, so if you’re coming to the article from a later step – please feel free to skip ahead! When I was in sixth grade, I was bullied pretty consistently by one specific person. I walked around the hallway each day for several months fearing that he would corner me and attempt to intimidate me. He never hit me or physically attacked me in any way, but the threats were so consistent that it ate away at my ability to reason. He threatened that if I ever told anyone, I’d be in serious trouble. So I didn’t. Eventually it stopped, but the remnants of the feelings I had while being bullied still live on in me today. When I was a summer camp counselor, I bought fully into the “zero tolerance” approach that’s very common in schools today. Any time I witnessed any bullying, I would take the bully aside and, well, bully him. I’d use threats that he would be sent home from camp, told him that his parents would be disappointed in him, and told him that I was disappointed in him. Sometimes this worked, and I’d pat myself on the back. Sometimes it didn’t, and I would consider the bully a lost cause, figuring that I’d at least tried my best. I used this approach through 2006, and thought myself a proper crusader against bullying. A real knight in shining armor. But then the data came in To many people’s surprise, including mine, the use of zero-tolerance policies has shown to have no effect at best, and negative effects at worst. With everyone from the NEA to the APA coming together in opposition to zero tolerance policies, it’s pretty surprising that such policies are used in so many environments. To be clear, I know that the implementation of zero-tolerance policies comes from a good place. People see a real problem in the world, and seek to fix it. They see someone whom they believe to be an aggressor, and someone whom they believe to be a victim, and attempt to intervene. As a former bullied person and zero-tolerance warrior myself, I totally get it. But it isn’t working. The only real effect that zero tolerance policies seem to have is to create the illusion in the minds of the enforcers that something is being done to solve the problem. Something’s being done, but it’s solving nothing. The ounces of prevention Now, I understand that it’s not always possible to stop bullying before it starts. We dealt with a bullying issue last summer that still troubles me. It felt like it shouldn’t have been possible, but there it was. I suppose it’s important to always remind ourselves, as camp directors, that we’re ultimately in control of a lot less than we think we are. But there are things that we can do – real things – with demonstrable results. I’d like to share them with you, and share why I feel I can advertise my camp as the “safest place from teasing and bullying on...

read moreOn “Kids Today,” how Teenagers Saved the Human Race, and What We’re Doing About it.

How I stopped blaming kids for not liking camp, and how that changed everything. Roger Sterling: I bet there were people in the Bible walking around, complaining about “kids today.” Don Draper: Kids today? They have no one to look up to. ‘Cause they’re looking up to us. This moment in the TV series “Mad Men” hit me like a ton of bricks the first time I witnessed it. Earlier in that very same day, I had returned home from doing some after-school tutoring in an urban church, and I had been lamenting how unfocused the kids seemed to be on their homework. They wanted to look at Pokémon cards, or talk to each other, or do ANYTHING besides the homework they were there to do. When describing the situation to my wife, I’m pretty sure I literally said, “In MY day…” And then I saw this episode, and I winced. It made me think – what if the problem hasn’t always been with kids, but instead with the society we’d structured for them? What if the problem wasn’t the kids I was mentoring, and the problem was with me? Flash forward a few years, and I’ve gained some considerable context to this issue. I’ve learned that this sort of frustration is far from new. Prehistoric Teenage Angst For generations, people have been wringing their hands about the troubled youth of the past. In the phenomenal work Overschooled but Undereducated, John Abbott puts forth that even in hunter-gatherer times, teenagers were reviled for their change-minded attitudes, and their desire to “fix things that weren’t broken.” Teenagers, he says, have always been the harbingers of change, and adults have generally been the proponents of the status quo. Evolutionarily, this makes sense. Once an adult has reached a point in his life where he is relatively secure, it’s going to take an awful lot to get him to change his perspective. Changing things when you are already surviving is a huge risk, and an unnecessary one. So why do teenagers seem so hard-wired to rebel? Because they are hard-wired to rebel. I’ll explain. Abbott cites neuroscience research that shows that the adolescent brain is actively destroying and rebuilding between 1.5%-2.0% of its brain cells every year – which leads to the characteristic intense and questioning behavior that we identify with adolescence today. This behavior, for most, is annoying for adults who think they know best for the child in question. Abbott suggests, however, that this reluctance to accept the way things are has literally saved humankind again and again. When there’s a glacier that threatens to destroy your tribe, it isn’t the adults with the comfy caves who lead the charge to get away. Abbott cites anthropological evidence that suggests that teenagers have almost universally been the ones who noticed problems in prehistoric communities, and the ones who struck out while the rest of their ancestors were doomed. Their willingness to change was reproductively advantageous, and no matter how much adults clacked their tongues, teenagers’ willingness to ignore their naysaying predecessors and follow their instincts has led us to where they are today. Prehistoric teenagers who were obedient, good listeners, died in whatever plague or environmental disaster killed the rest of their communities. And only the rebels lived on. What happens...

read moreHow I learned Offering Kids Choice is so Important

How offering campers choice got rid of so many common camp problems A bad plan, some unlikely friendships, and a new outlook When I decided to take a job at a new camp 3 years ago, I had a very sneaky plan. Quite simply, I planned to change the camp where I was moving into the camp I was moving from. I knew they’d be resistant to these changes at first. After all, change is hard. But I came from the best camp that ever existed, and even though change would be hard for them, I knew it was in their best interest. I called a respected friend in the camping industry, and he gave me what I now know is “best practices” sort of advice. “James,” he said, “your plan stinks.” (paraphrased this, but the idea is the same) I was bewildered. My plan did not stink! This camp needed saving, and here I was, ready to save! This camp couldn’t wait! It needed to be changed right away! I continued listening, and rolled my eyes (which he couldn’t see, because we were on the phone). He continued. “They’ll hate you if you change everything right away. No matter how good your ideas are, the people who are still at that camp like it the way it is. If you want to change something – add things to the camp, but don’t take anything away.” Hmm. This actually made sense. I started thinking about what would be “too big a change,” and what would feel more like an “addition” to the program. I started tinkering a little bit, but there was one thing I was having trouble reconciling. I was a dyed-in-the-wool, small group camping zealot. And this new camp? They let kids choose their own activities, and separate from their cabin groups throughout the day. I was aghast. How could they form any relationships? How could they learn to deal with people they didn’t like? How did this camp prevent cliques from forming? I knew this would be too big a change, so I held my nose, and prepared for a summer of dystopian camp hell. But then something happened. The first full week of camp, an absolutely mind-altering group of friends formed. Three kids – ages 10, 13, and 15. The ten year old was diagnosed with a handful of things, and her social skills were developmentally behind schedule. The 15 year old was a young man who suffered from both physical and learning challenges. The third, while not classically diagnosable, was definitely a “march to the beat of her own drum” type. Each of them, I knew, would have been outcasts in their groups at my old camp. Tolerated, sure. But forming these incredible, enduring friendships? The times I had seen kids similar to these form such friendships were exceedingly rare. And I realized something. If I had changed this camp’s structure, these kids would likely have never met. The only reason they did meet, and grow to love one another, was because they had the choice to interact with whom they pleased. I had some thinking to do on this whole choice thing. If choice is good enough for me, why isn’t it good enough for them? Shell-shocked at realizing I was losing my...

read moreBoiling down the “why” of your summer camp

The ever elusive “Why?” Now, something like a thousand books have been written on the subject of finding the “Why” of an organization, and whenever I’ve brought it up with people, I’ve gotten glassy-eyed agreement that, of course, starting with “why?” is what any organization should do, and of course, that’s what their organization does, and so on. I remember feeling exactly this way when a consultant came to a camp where I was serving as a member of the board of trustees. You see, we had been struggling for several years. Camper numbers were declining, revenues were slipping, and we just couldn’t seem to steer the camp back toward growth. Oh, we had plenty of reasons why our camp was shrinking, they had just happened to have nothing to do with us. Kids are so busy during the summer time. Parents don’t understand the value of camp. Kids play too many video games. Publicly subsidized camp options were so cheap. Kids were too coddled and didn’t enjoy being away from home. You get the idea. So when this consultant came in and told us to “start with why,” we politely tolerated his line of questioning, and then literally laughed when he left the room. We wanted tactics. Marketing plans. Budgeting advice. Cheaper places to buy paper. We didn’t want to sit and do a bunch of hoity-toity hippy-sounding “why”ing, man. WE knew why our camp was there. Wasn’t it obvious? Everyone in the room absolutely loved camp. Camp was great. “What’s the why of your camp?” Give us a break! The why is obvious! The why was… We just moved on from the discussion without ever biting into the meat of the consultant’s question. We got back to trying to figure out the “How” of righting the ship of our camp, not this time-wasting “why.” And, once again, we were unsuccessful. Like probably everyone at camp, we had an internal concept of what the “why” of our camp was. Of why a kid should go there, or a parent should trust their kid with us. We had a mission statement and everything. Most of us had attended the camp as kids. We had a deep sense that camp was really, really important. But we had no concrete list of why our camp was important, or why a parent should choose our camp, instead of one of the 10 camps in a 5 mile radius. And here’s the real kicker: If you can’t communicate why a kid should come to your camp instead of choosing any of the other infinite possibilities she has during the summer, chances are pretty good that she’ll choose one of those other possibilities instead. So let’s take a step back and figure out the real why of what a camp is, and what doors are opened up when one finally distills the why of a camp. I recently met with two of the most incredible camp people I know, Jack and Laura from Camping Coast to Coast. I have the amazing opportunity to work with them this summer (2014), and the very first discussion we had before diving into any detail about this summer (including what their jobs will be) was figuring out the “why” of Vanderkamp, where I work. Why are we here?...

read more