How I stopped blaming kids for not liking camp, and how that changed everything.

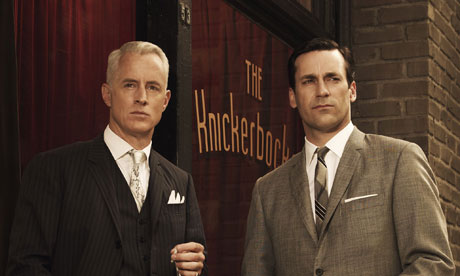

Roger Sterling: I bet there were people in the Bible walking around, complaining about “kids today.”

Don Draper: Kids today? They have no one to look up to. ‘Cause they’re looking up to us.

This moment in the TV series “Mad Men” hit me like a ton of bricks the first time I witnessed it. Earlier in that very same day, I had returned home from doing some after-school tutoring in an urban church, and I had been lamenting how unfocused the kids seemed to be on their homework. They wanted to look at Pokémon cards, or talk to each other, or do ANYTHING besides the homework they were there to do. When describing the situation to my wife, I’m pretty sure I literally said, “In MY day…”

And then I saw this episode, and I winced. It made me think – what if the problem hasn’t always been with kids, but instead with the society we’d structured for them? What if the problem wasn’t the kids I was mentoring, and the problem was with me?

Flash forward a few years, and I’ve gained some considerable context to this issue. I’ve learned that this sort of frustration is far from new.

Prehistoric Teenage Angst

For generations, people have been wringing their hands about the troubled youth of the past. In the phenomenal work Overschooled but Undereducated, John Abbott puts forth that even in hunter-gatherer times, teenagers were reviled for their change-minded attitudes, and their desire to “fix things that weren’t broken.”

Teenagers, he says, have always been the harbingers of change, and adults have generally been the proponents of the status quo. Evolutionarily, this makes sense. Once an adult has reached a point in his life where he is relatively secure, it’s going to take an awful lot to get him to change his perspective. Changing things when you are already surviving is a huge risk, and an unnecessary one.

So why do teenagers seem so hard-wired to rebel? Because they are hard-wired to rebel. I’ll explain. Abbott cites neuroscience research that shows that the adolescent brain is actively destroying and rebuilding between 1.5%-2.0% of its brain cells every year – which leads to the characteristic intense and questioning behavior that we identify with adolescence today. This behavior, for most, is annoying for adults who think they know best for the child in question. Abbott suggests, however, that this reluctance to accept the way things are has literally saved humankind again and again.

When there’s a glacier that threatens to destroy your tribe, it isn’t the adults with the comfy caves who lead the charge to get away.

Abbott cites anthropological evidence that suggests that teenagers have almost universally been the ones who noticed problems in prehistoric communities, and the ones who struck out while the rest of their ancestors were doomed. Their willingness to change was reproductively advantageous, and no matter how much adults clacked their tongues, teenagers’ willingness to ignore their naysaying predecessors and follow their instincts has led us to where they are today.

Abbott cites anthropological evidence that suggests that teenagers have almost universally been the ones who noticed problems in prehistoric communities, and the ones who struck out while the rest of their ancestors were doomed. Their willingness to change was reproductively advantageous, and no matter how much adults clacked their tongues, teenagers’ willingness to ignore their naysaying predecessors and follow their instincts has led us to where they are today.

Prehistoric teenagers who were obedient, good listeners, died in whatever plague or environmental disaster killed the rest of their communities. And only the rebels lived on.

What happens when we stop blaming kids, and start understanding them.

Looking at “kids today” and what interests them without judgment can be really difficult. I know it can for me. My eyes go wide with mild outrage every time I’m talking to a young person and they are texting someone else WHILE TALKING TO ME. Like, while words are coming out of their mouth. Every time a summer camper sends me a request to play Farmville, a little piece of me dies inside. When I return to my home neighborhood, and don’t see a single kid out on a bike, I feel a deep sense of loss.

I used to point to these observations as a clear indicator that we were barreling toward a dystopian future. I did so even more when looking at my summer camp numbers each year. Sure, they were going down, but it wasn’t my fault! It was this newfangled technology! It was parents for allowing kids to have cell phones at 8 years old! It was schools for making sure no one ever failed, or little leagues who gave out trophies for 8th place, or… anyone, except for me.

But all this blaming wasn’t helping my camp. It wasn’t helping me connect with kids. The world was turning, and leaving me and people like me behind. Camp seemed like the last frontier of all that was good – the last place where we could really save “kids today.”

So when I took my job at Vanderkamp, I came with all of this “kids today” and “society today” baggage. I was dead set on preparing kids for the so-called “real world.” They were going to like camp, damnit, whether they wanted to or not!

But when I got here, something funny was going on. The kids were – gasp – sleeping in houses! Instead of the platform tents and rustic cabins that I grew up with! How could anyone experience camp, I wondered, if they didn’t have to trudge through the mud to go to the bathroom? Where would the bonding happen? Why wouldn’t we just do camp in a hotel!?

But when I got here, something funny was going on. The kids were – gasp – sleeping in houses! Instead of the platform tents and rustic cabins that I grew up with! How could anyone experience camp, I wondered, if they didn’t have to trudge through the mud to go to the bathroom? Where would the bonding happen? Why wouldn’t we just do camp in a hotel!?

I set to work outlining a plan to get camp out of these estate houses within 5 years. I couldn’t do it at first, of course, because everyone would hate me. But my plans were laid, and we went into the first summer.

Then, something weird happened. Camp in these houses was… kind of awesome. They fostered a ton of community (with 20 kids in a single building). They allowed kids to interact more frequently. They cut down on travel.

But the biggest advantage? Kids didn’t hate them.

Summer campers here are challenging themselves a ton just by watching mom drive away. They aren’t as acclimated to the outdoors as I was as a kid, so sleeping in a tent and getting mosquito bites all night is a challenge that is sort of besides the point. I’m a “start with why” zealot, in case you haven’t noticed, and the “why” of my camp just isn’t to get kids to enjoy sleeping in a tent. It’s about helping them learn to love themselves, to challenge themselves, to learn to use freedom wisely, and to love others. I realized that the magic of what was happening here was happening because they weren’t distracted by being extremely uncomfortable. And this was a beautiful thing.

I returned to my board with my tail between my legs, telling them that sleeping in these houses was actually an incredible advantage that we had. That we were challenging kids, and helping them grow in so many ways by eliminating one unnecessary challenge that was beside the point. Kids were still spending all day outside, pretty much – they just didn’t have to worry about a raccoon crawling in their sleeping bag at night time. Since my board is awesome, they shrugged their shoulders and said, “Whatever you say!” It was a real bullet dodged, and a huge lesson learned.

What else was I missing?

If you haven’t had to stand in front of a board and say “I was totally wrong” about something you made them spend hours mapping out, I highly suggest it. What a humbling experience. As someone who sort of has a hard time being wrong, it made me look very carefully at other positions I feverishly held in case they were wrong, too.

When I started debriefing the summer, I came to the conclusion: there were lots of ways I was refusing to change the way I worked with kids, in spite of their direct and negative feedback on certain things.

What we did about it

So, we did something pretty radical. Something that might not work for everyone logistically, forget about philosophically. We decided to take our “why” to its extreme. If we were going to change kids to be their best self instead of change them to be what we thought their best self should be, we needed to listen to them.

We needed to STOP being one of those businesses that blames its customers for not liking it. Those businesses die, and our “why” was too important to die.

When we really stripped things down, we decided that kids were challenging themselves simply by setting foot on camp. We didn’t need to force them to make new friends – they were doing this on their own. We didn’t need to force them to try new things – simply being at camp was a new thing, and forcing them to try other ‘new things’ might actually have the reverse impact that we were going for.

We went for a system of total freedom. If campers wanted to do something – it only had to meet 3 guidelines:

1) It couldn’t physically endanger anyone.

2) It couldn’t emotionally harm anyone.

3) It couldn’t be something that would horrify their parents.

Everything else? Fair game.

This approach had some awesome unintended consequences. First, kids showed us that when there are few, but extremely consistent guidelines, they are more than happy to follow what few rules we have in place. We’d avoided being like the grown ups in Charlie Brown cartoons. When we stopped getting on kids about all these little things, they were seeing and hearing us on big picture stuff in a way they never had before.

Another amazing unintended consequence? It made us up our game. When kids are free to sit and chill with their friends (perhaps for the first time in their lives), you better have some awesome programmatic offerings. When kids can stay up as late as they want, you better have something worth waking up for. When kids can choose between a hike and talking about video games, your hikes have to be EPIC. My counselors blew me away in this regard. They knew something was at stake – and came up with some incredible ideas that have kids at Vanderkamp spending more time connecting with the outdoors than they were even before we went whole-hog with freedom.

Showing Kids that you’re “one of them”

Teenagers, and young people in general, are seeking change. They always have been. Sure, we all believe we have things we can impart to campers to make them find their best self more quickly. We wouldn’t be in camping if we didn’t. For us, though, showing teenagers that we wanted to be partners in their journey to change the world as opposed to trying to change them to be of the world has meant everything.

Kids love camp because it’s likely the first place they’ve found adults who don’t care about anything besides how kindly they are interacting in the community. This is something they can get behind. For the first time, there is no pressure to be smarter, or faster, or better looking.

Creating communities like this is the “why” of camp for so many of us. Remembering that this is why, given all of their other options, kids continue to choose us over video games, and texting, and the rest of their incredible options is such an inspiration to me. Looking a young person in the eye, seeing that deep hunger for change, and lending a hand up instead of a disapproving head shake has changed my relationship with young people forever.

So when people say “Kids today,” I’ve stopped nodding my head knowingly. Instead, I just give a little smile, and say, “What about us?”

Are you ready to grow your camp and change more lives?

This is an awesome and revolutionary article. Every youth minister should read and discuss this with their youth committee!!!

Thank you so much for the kind words! 🙂