How offering campers choice got rid of so many common camp problems

A bad plan, some unlikely friendships, and a new outlook

When I decided to take a job at a new camp 3 years ago, I had a very sneaky plan. Quite simply, I planned to change the camp where I was moving into the camp I was moving from. I knew they’d be resistant to these changes at first. After all, change is hard. But I came from the best camp that ever existed, and even though change would be hard for them, I knew it was in their best interest. I called a respected friend in the camping industry, and he gave me what I now know is “best practices” sort of advice.

“James,” he said, “your plan stinks.” (paraphrased this, but the idea is the same)

I was bewildered. My plan did not stink! This camp needed saving, and here I was, ready to save! This camp couldn’t wait! It needed to be changed right away! I continued listening, and rolled my eyes (which he couldn’t see, because we were on the phone). He continued.

“They’ll hate you if you change everything right away. No matter how good your ideas are, the people who are still at that camp like it the way it is. If you want to change something – add things to the camp, but don’t take anything away.”

Hmm. This actually made sense. I started thinking about what would be “too big a change,” and what would feel more like an “addition” to the program.

I started tinkering a little bit, but there was one thing I was having trouble reconciling.

I was a dyed-in-the-wool, small group camping zealot. And this new camp? They let kids choose their own activities, and separate from their cabin groups throughout the day.

I was aghast. How could they form any relationships? How could they learn to deal with people they didn’t like? How did this camp prevent cliques from forming?

I knew this would be too big a change, so I held my nose, and prepared for a summer of dystopian camp hell.

But then something happened.

The first full week of camp, an absolutely mind-altering group of friends formed. Three kids – ages 10, 13, and 15. The ten year old was diagnosed with a handful of things, and her social skills were developmentally behind schedule. The 15 year old was a young man who suffered from both physical and learning challenges. The third, while not classically diagnosable, was definitely a “march to the beat of her own drum” type. Each of them, I knew, would have been outcasts in their groups at my old camp. Tolerated, sure. But forming these incredible, enduring friendships? The times I had seen kids similar to these form such friendships were exceedingly rare.

And I realized something. If I had changed this camp’s structure, these kids would likely have never met. The only reason they did meet, and grow to love one another, was because they had the choice to interact with whom they pleased. I had some thinking to do on this whole choice thing.

If choice is good enough for me, why isn’t it good enough for them?

Shell-shocked at realizing I was losing my “small group camping zealots” membership, I returned home to my wife and discussed what I was observing.

It wasn’t just these three kids who were relishing being offered choice over their activities. It was… everyone. Arts and Crafts was more fun because nobody there was complaining that it was boring. Sports were more fun because everyone there was comfortable with competition, and they weren’t forced to be there. A wacky idea that would have received eye-rolls from a full group of everyday campers went off like gangbusters with 7 kids and 2 over the top counselors. Kids were simply having a TON of fun.

And what was more – those three kids weren’t the only ones forming friendships outside of their cabin groups. 2 young girls had latched on to a group of teenage girls, who were spending their times giving piggy back rides and doing face paint instead of focusing on teenage drama. My wife reminded of research she had encountered years before, on the benefits of mixing ages in classrooms, and it really all clicked.

I didn’t need to look any further than my own life to see how much I preferred choosing my friends and activities than being forced into relationships I didn’t want or into activities that I didn’t choose.

I invite you to look into your life, as well. What was the best part of your day today? Got your answer? Was it during a time when you were doing something that was planned for you by your boss, a teacher, your parents, or your spouse? No?

My guess is that you’re like me, and it was most likely something you did of your own free will. It makes sense, right? You know you better than anyone else possibly can – even people who really want to help you have fun.

Virtually everyone relishes the freedom in their lives. Why, then, did I assume that my camp staff and I could better plan a child’s day and her friends better than she could?

Confidence Grows from Choice, not Force

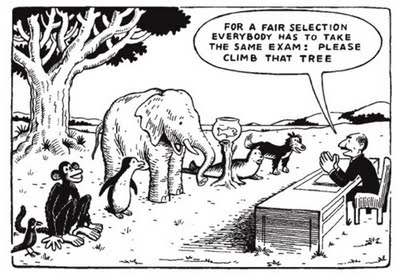

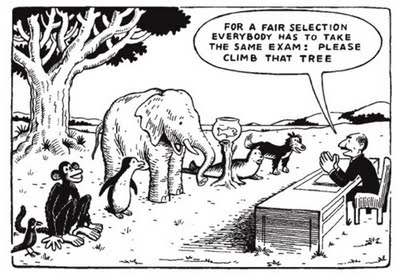

Albert Einstein famously said, “Everybody is a genius. But, if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

Albert Einstein famously said, “Everybody is a genius. But, if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

By structuring not only the activities a child must do, but also the people a child must interact with, we send a child an unintended message about himself: Don’t trust your own instincts – let adults show you what is right.

When kids come to camp, having pre-determined activities sends a clear message: these are the things that are important. In Einstein’s fish example, you can imagine a fish getting pretty down on itself if it thinks that climbing trees is the end-all be-all. Happily for fish, they are typically left to their own devices. Unhappily for our children, they most certainly are not.

Now, we still offer structured activities for kids, and we make guesses about what we think we can do best for them. We typically offer four or five activities to choose from (depending on the number of kids), and we even added a special twist.

When we offer activities, we keep a couple of staff around to observe, in case there is a group of kids who doesn’t seem to be connecting with any of the offerings. If such a group arises, these kids are approached and given a blank slate to do whatever they want. Sometimes they choose to sit and talk. Sometimes they want to go to the unstructured play area. If we can make it work logistically, we do.

My plan to change the camp? Well, I did wind up changing it, but not in the way I expected. Instead of axing camper choice, I decided to add MORE of it.

In fact, we decided to try and stop guessing as to what kids wanted, and turn some activities entirely over to them. We hang up a simple Camper-led adventure sheet (download by clicking the link), and make kids aware of it. If they can get 4 friends to sign up to do the activity with them, we’ll offer it the next day. Sometimes it requires clarification. I had never heard of Dr. Who, and couldn’t picture what a “Dr. Who Meet-up” was supposed to be. I had no idea that 35 kids would want to sit and make inside jokes about Dr. Who. But they did, and they loved it.

When kids have this kind of control over their environment, they transform from the audience of a performance to the creators of a performance. They conspire with one another to come up with exciting activities. They write in-depth outlines as to how their activity will work to try and rally excitement.

And when their activity goes off, and other kids are having fun too? It’s just amazing to see the confidence that comes with it.

The Camp I’d want to attend

When I think about offering the best possible summer camp experience, I can’t look further than the type of camp I’d want to attend. Would I want to go somewhere and be told with whom to interact? What I could do?

I imagine how painful it would be to attend a camping conference, and be given an itinerary of workshops I had to attend, and who I’d be eating meals with. Can you even imagine?

I can’t, either.

I realized that the main reason I wanted to prescribe activities for kids and tell them with whom to spend their time was because I thought I could tell them how to spend their time better than they could figure it out for themselves. I really, really cared about kids – and I thought I could use my experience to offer them more than they could find on their own.

I worried that a choice based model wouldn’t challenge them, wouldn’t “prepare them for the real world,” wouldn’t encourage them to try something new.

But what I saw when I came here? Kids were challenging themselves. They were preparing for the “real world” by making “real world” choices. And they were really trying something new. They were experimenting with what it was like to be trusted to pursue what interested them.

Great Stuff